gint aras

author of Relief by Execusion

Gint Aras (Karolis Gintaras Žukauskas) has been trapped on planet earth since 1973. His writing has appeared in Quarterly West, St. Petersburg Review, Curbside Splendor, (Re)Imagine, STIR-Journal and other publications. His novel, The Fugue, was a finalist for the 2016 Chicago Writers Association’s Book of the Year Award. He lives in Oak Park, Illinois.

now available

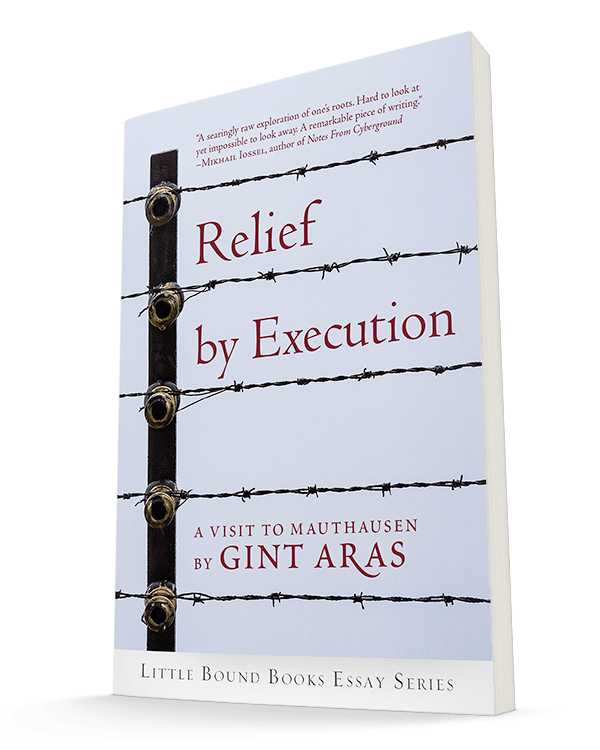

Relief by Execution: A Visit to Mauthausen

Paperback | Size: 4 x 6 | Length: 80 pgs | | List Price: 12.95

Offering in the Little Bound Books Essay Series

_______________________

Available in Paperback and ebook.

*Receive 20% off when you purchase in our store

+ Free shipping on orders over $40.00 with coupon code: INDIESTRONG

About

the book

Between the years of 1996-1999, Gint Aras lived a hapless bohemian’s life in Linz, Austria. Decades later, a random conversation with a Polish immigrant in a Chicago coffeehouse provokes a question: why didn’t Aras ever visit Mauthausen, or any of the other holocaust sites close to his former home? The answer compels him to visit the concentration camp in the winter of 2017, bringing with him the baggage of a childhood shaped by his family of Lithuanian WWII refugees. The result is this meditative inquiry, at once lyrical and piercing, on the nature of ethnic identity, the constructs of race and nation, and the lasting consequences of collective trauma.

“A searingly raw exploration of one’s roots. Hard to look at

yet impossible to look away. A remarkable piece of writing.”

–Mikhail Iossel, author of Notes From Cyberground

“This is blistering nonfiction. It features a vulnerability reminiscent of The Glass Castle and a personal exploration so intimate that to read Relief by Execution feels like having it read to you by Aras, sitting in an armchair opposite some glimmering fire.”

–Michael Prihoda, After the Pause

Read the first pages

Relief by Execution

I sense a deep connection to the dead any time I stand on cobblestones in Europe. Unlike the common asphalt of American streets—their cracks tarred only months after the blacktop has grayed—cobblestones are cut to outlive their makers by centuries. More dead than living have walked the cobblestones at the market square here in Linz, Austria. Hardly the oldest city in Europe, Linz’s architecture still shows the city’s builders are long dead. A palace already standing in 799 looks over the Danube, and a plague column, erected in 1690, thanks God for stopping pestilence.

It’s an early morning in December of 2017, and I’ve returned to visit Linz after living here between 1996-99. I’m the first customer to enter a bakery where I drink strong coffee and eat crusty rolls with jam. Unable to sleep last night, I had left my hotel before sunrise, plenty of time to make my morning train to Mauthausen, only 30 minutes east. I am 44 years old, born in America in 1973, and while I have lived and worked in two European countries, today is the first time I will ever set foot in a Konzentrationslager-Gedenkstätte, or Concentration Camp Memorial.

I’m not visiting the camp out of interest in history. I have been meditating over a chosen task for months:

I won’t enter the camp to imagine myself a victim, visualize how it should feel to be interned. Instead, I will be the atrocity’s perpetrator. The prisoners before me must suffer extermination because they are my inhuman enemies.

The seeds for this moment were planted before my birth. I’ve inherited energies from predecessors and elders, their ideas and feelings headed for my body long before I’d been conceived. While my knees feel a bit heavy, they don’t stop me moving. I’m already at the train station, looking for the right platform.

****

To explain what this is all about, let’s begin with a child caught in a trap.

It should seem impossible for the child presently being beaten by his father to possess any power at all. You’d think those aware of the beating would want the father set apart from the child, as many people, from my mother to grandparents and sundry elders, know what he is doing. Yet no one sets us apart.