Frank Larue Owen

Award-winning author of The School of Soft-Attention, Temple of Warm Harmony and Stirrup of the Sun & Moon

Frank Inzan Owen (Hidden Mountain) is a Wayfarer of a Nature-oriented contemplative path shaped by philosophical Daoism, solitary Zen, and mountains-and-forests spirituality. This path, in turn, exerts a strong influence upon his poetry and evolving creative life. He is the author of three books of poetry, all on Homebound Publications, The School of Soft-Attention, The Temple of Warm Harmony, and Stirrup of the Sun & Moon. When not tending a year-round organic garden, hillwalking in the north Georgia Piedmont, or curating content for his publishing streams, Hidden Mountain Studio and The Poet’s Dreamingbody, he facilitates a form of Jungian-informed innerwork he calls contemplative soulwork through his organization, The School of Soft-Attention.

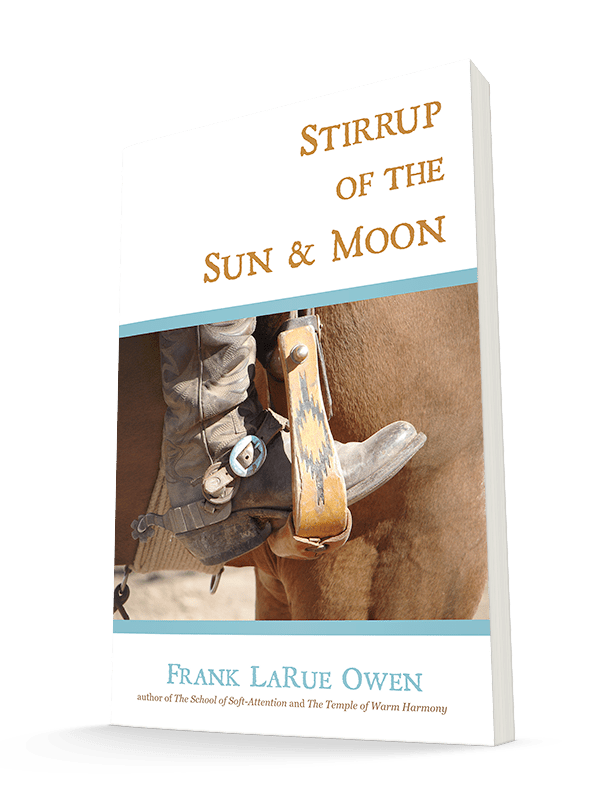

newest offering

Stirrup of the Sun & Moon

Paperback | Size: 6 x 9 | Length: 120 pgs | | List Price: 16.95

We Two-Leggeds are not limited to a physical body. We have capacities of perception beyond the usual five senses. Landscapes — inner, outer — can hold wisdom, healing-energy, memory, and teachings. A practice of attunement to the spirit of place is one viable path for the activity of a poet.

So begins Stirrup of the Sun & Moon — a collection of poems rooted in the seasons, landscape, ancestry, memory of place, and the churning gyre of the soul. As you make your way through Frank LaRue Owen’s third book of poetry, you will notice two features — both inspired by customs from early Chinese poetry — that orient and augment the poems. Every poem (with the exception of one) was composed be read with music and contains a liner note that includes the name of a song, its album, and composer. Additionally, some of the poems are place-centric and include the name and place coordinates associated with the poem. As you travel through Stirrup of the Sun & Moon, you will encounter poems-as-memory and poems-as-markers on a map, inspired by such diverse places as Northern California and Colorado, Mississippi and New Mexico. Saddle up!

_______________________

Available in Paperback and ebook.

*Receive 20% off when you purchase in our store

+ Free shipping on orders over $40.00 with coupon code: INDIESTRONG

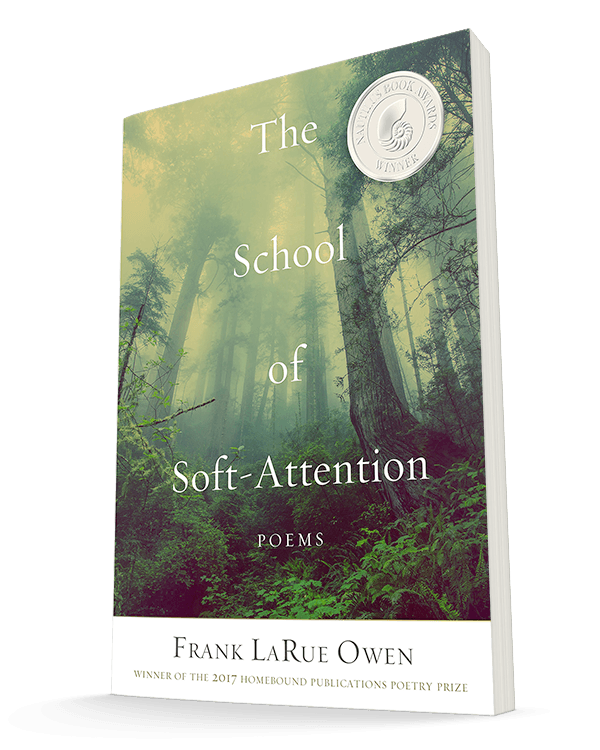

award-winning

The School of Soft-Attention

Paperback | Size: 6 x 9 | Length: 116 pgs | | List Price: 16.95

Winner 2017 Homebound Publications Poetry Prize

Winner 2018 Nautilus Silver Medal for Poetry

_______________________

Available in Paperback and ebook.

*Receive 20% off when you purchase in our store

+ Free shipping on orders over $40.00 with coupon code: INDIESTRONG

About

the book

It has been said that poetry can be a marker of where a poet has been, or a way for a poet to point to places where we, the reader, can go. Both types of poems appear in The School of Soft-Attention. Not corralled to any one poetic style, the heart-mind-river that forms this flowing collection has been shaped by the author’s diverse cross-cultural experiences, spiritual tutelage with a New Mexican wisewoman and wilderness guide, and fueled by such practices as meditation in the Zen tradition, mountain pilgrimages, fasting in the deserts of New Mexico, and intensive dreamwork. At every point along the way, the poems in The School of Soft-Attention invite the reader to turn to a new way of seeing, a new way of paying attention to the life within and around us.

“The Zen-influenced poetry of Frank LaRue Owen comes from a place of great emotion, restraint, and insight. His work honors the memory of his teachers, with words of encouragement that move the mind forward, while still mindful of the travails of the present. I am honored that Mr. Owen uses my music during his creative process and has shared his work with me. His short poems function much like music that wafts in and out of a listener’s consciousness, in an abstract realm of understanding.”

-Forrest Fang, Chinese-American composer, ambient musician

“With echoes of Tufu, Basho, Thoreau, Gary Snyder, Mary Oliver, and others, yet with a voice throughout that is authentically and distinctively his own, Frank LaRue Owen’s The School of Soft-Attention gracefully incorporates many influences, both ancient and modern, East and West, Japanese Zen, Chinese Taoist hermit, Native American, to name just a few. I am moved and impressed.”

–Frank W. Berliner, author of Falling in Love with a Buddha and Bravery: The Living Buddha Within You

Read the first pages

Preface

The Dao of Receiving

“A man doesn’t go in search of a poem;

the poem comes in search of him.”

–Yang Wan-Li

Outside: gray day, dark clouds, white frost on branches.

Inside: I sit wrapped in a blanket beside a rain-dappled window gazing up at the swaying sentinel pines, contemplating Dao.

A black-capped chickadee, adorned with all the same colors of this day, darts in and out of view. Flowing with the moment, a thought stirs like feathers ruffling:

Heart-Mind, left to its natural state, is vast as a panorama of Nature.

If settled, receptive, a poem may arrive like the seed-hunting chickadee flitting through.

A splash of color. A flash of life and movement. A brief moment in this shared dream. Are we truly present to receive it? This is the path, on this gray day, and every other day.

Words emerge from the silent illumination of the wordless Dao.

Yet, words can never be complete.

I often ponder the mysterious phenomenon that is poetry; even more than I write it. From the old Daoist and Chan poets of China and haiku and haibun poets of Japan, who often gazed at mountains and were stirred to brush a poem after sitting in meditation, to modern-day wayfaring, activist, and eco-poets of today, there seems to be a true common denominator among them all. Poetry is inseparable from awareness and spirituality.

Whether I write a poem or not, the practice of inner-outer observation is part of the daily course. It’s part of the heart-mind of Dao-trackers. It’s inseparable from the Zen mind of tea masters. It’s part of the luminous tapestry of indigenous earth-spirit traditions where ‘second-attention’ is cultivated. It’s a current that flows through American eco-poetry and even some of the cowboy poetry of the American West. So, as a lifetime student of consciousness, and a writer of poetry, it is natural to me to see poetry as a path of observation, as a way of working with dreams, as a practice for connecting with Nature. Poetry is one of the indispensable elements of our universal human heritage.

Poetry can also be a means of initiation for both poet and reader, spurring what some Jungians call innerwork. Poetry brings people together into community. Poetry is an experience of consciousness. Poetry is a way of seeing, a way of listening, a way of hearing with the whole body and soul. Poetry is rooted in what Rev. Dr. Joey Shelton calls “holy noticing.” From the Mazatec curandera Maria Sabina to the ancient Zen hermit-poet, Stonehouse, all contemplative and earth-spirit traditions and their subsequent expressions of poetry meet at the trailhead of such holy noticing.

In gathering the poems for this book, I circled back around to another idea of poetry held by one of my late teachers, doña Río, who said poetry is “an ongoing curriculum offered by the life around you and within you.” Though not a published poet herself, doña Río was a seasoned practitioner of her path of poetry-as-observation. She was a master of paddling her “spirit boat” through the river of heart-mind, guiding others through theirs, and using poetry as a way to process experiences on her unique cross-cultural spiritual path, which was shaped by indigenous/Mesoamerican worldviews and her practice of Zen meditation. If it weren’t for her, and other poet-teachers I crossed paths with along the way, like Bill Scheffel and the late Jack Collom, there might not be any poems in this book.

~

I first encountered a poetry that moved me on the cusp of my teen years, nearly four decades ago. It was a verse from the great haiku master of Japan, Matsuo Bashō, author of Narrow Road to the Interior, the classic travel journal blending spiritual prose, travel observations, and haiku poetry. Most people who know of Bashō know of his famous poem about a frog leaping into the water, of which there are innumerable translations. The most often quoted in the public domain: old pond…frog jumps in…sound of water. That was not the first verse of Master Bashō I encountered, however. It was this one, and it split me open like a gourd:

“Seek not the paths of the ancients;

seek that which the ancients sought.”

When I read these words as a pre-teen, it was not a “normal” reading. It was a lightning strike. The phrase struck and sizzled down my spine and was followed by a gentle sense of relief that washed over me like a cool breeze in summer. Bashō’s words woke me from my human trance. I experienced it as a source of direct instruction; a liberating decree from an elder; a personalized sanction to chart one’s own course in creative and spiritual matters; a universal outflow of permission to faithfully follow where the soul may lead. As I ponder my approach of the same age that Bashō was when he died in 1694, it strikes me that, in many ways, I owe my whole path of poetry to Bashō. Even though I am not a poet who focuses on his poetic form of haiku (short, three-line poems with a 5-7-5 syllable structure), it is the wandering heart-mind of Bashō to which I am forever grateful, and is one of the spirits that spurs me onward.

When I learned that Bashō trained for a time in Zen, was highly influenced by themes from Buddhism and Daoism, and took daily inspiration from the works and life of a hermit-poet named Saigyō, a wandering Buddhist priest who preceded Bashō by 450 years but whom Bashō earnestly felt was his teacher, I began reading everything I could about Zen, nature poetry, Chinese and Japanese poetic traditions specifically, and the legacy of global mystical, shamanic, and contemplative poetry in general. Soon, fully inspired, I began putting pen to paper myself.

In my late teens, I took up the formal practice of zazen (seated meditation of the Zen Buddhist tradition) after reading Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, a Zen classic first published in 1970, the year after I was born. Paired with zazen, I also had various experiences in ceremony with First Nations people including Anishinabe, Haudenosaunee, Lakota, Mayans, and Yaqui. Each culture has their own tradition of sacred words, songs, and poetry that affected me greatly. Likewise, I delved into a frequent practice of contemplative forest walking (now termed shinrin-yoku: “forest-bathing” in contemporary Japanese), an ancient practice being rediscovered today by the medical community but which has always been inseparable from the old Daoist and Buddhist hermit-poets of China, Japan, and Korea. For some reason, I knew instinctively to gravitate to this practice.

In the late-90s, after graduate school, my interest in the interface between mind-training, nonordinary states of consciousness, time in Nature, and poetry took on an added level of dimension and practice. I began a decade of study with an eclectic, somewhat reclusive teacher, whom I had met in Colorado but who had moved to New Mexico. Shaped by her own experiences with Mesoamerican, Native North American, and Japanese Buddhist paths (all traditions in which she studied and trained), doña Río’s path was characterized by a profound view of cosmos, Nature, the psychology of transformation, and a deep love of art, poetry, and wisdom wherever it may emerge in the cultures of the world. Doña Río’s mentoring of me at her red-earth adobe bungalow on Cerro Gordo in Santa Fe, in the forests and mountains east of the city, and in the arroyos of northwest New Mexico, was a significant influence on my practice of poetry; poetry as eco-poetics, poetry as dreamwork, poetry as earth-spirit experience, poetry as an expression of Dharma art, poetry as a contemplative practice of awareness and attention.

With her death in 2007, however, I suddenly felt like a small bird, with untested wings, kicked from the nest. For years, it felt like I was falling through the air. I had yet to trust the wind. If you had asked me then, I would have reported that I was floundering, drifting like a ghost inside my own life. I felt utterly groundless, and I was grieving.

I entered a phase of depression—a Dark Night of the Soul contemplative Christians call it—from having lost not only a dear friend but also a key reference point on the path I had been walking. Yet, for anyone working with an authentic spiritual teacher or artistic mentor or guide, that teacher will continue turning you back onto yourself rather than allowing you to collapse into the relationship or some kind of overzealous adoration. Spiritual and creative authenticity has no room for codependency; and, so, with doña Río’s death, I had nowhere else to go.

I was, once and for all, turned back onto myself. As such, following her teachings and the general markers of the path that she lived herself, I turned inward. I turned to the practice of meditation. I turned to idleness in Nature for healing my grief. I turned to an old Daoist and Buddhist practice used by hermits for thousands of years called the ‘Dark Retreat’ to seek some sense of stabilization from the painful turmoil I felt. It took me nearly another decade before I began to feel a sense of regaining what doña Río called practice-equilibrium.

Practice-equilibrium is more than a concept; it is a felt somatic experience that informs one’s creative and spiritual life. It applies to artists of all kinds including writers, poets, dancers, actors, visual artists, martial artists, yoga practitioners, practitioners of the Way of Tea, and meditators alike. The term does not mean that the hard knocks of life no longer affect the practitioner. Practice-equilibrium isn’t a fixed or static state, nor a permanent stage of development. You don’t achieve it one day and then go on autopilot. It is work.

Equilibrium, in this sense, is the ongoing practice of mindfully rebalancing when we are thrown off-center. If you’re an artist (of any kind), or paying attention to your life (as the artist of your life), then you are a practitioner, and being thrown off-center, especially in the world we live today, is part of the territory, part of the job description of the human experience. If anything, not taking the numbing path of pop-culture distraction of most modernistas, people who work with practice-equilibrium will often find that they feel things even more fully and intensely. We let life in, intentionally. We are the ones who willingly accept the life prescription of Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh who says: “Do not turn your eyes from suffering.” To do that, a constant, vigilant practice of rebalancing is needed. In this way, practice-equilibrium is rather more like the consciousness of a seasoned surfer. Conditions change, waves arise, and the practitioner, relying on practices that enable us to stay fully present with our experience, adjusts the “surfboard” of heart-mind.

After nearly a decade of solitary practice after my teacher’s death, I have found a refreshed practice-stride with all of the practices I studied with her, including poetry. With it has come full comprehension of something she was fond of saying. This comprehension arrived in similar fashion as the “lightning strike” of Matsuo Bashō’s verse about “seeking what the ancients sought.”

I opened an old journal of mine and found a quote of doña Río’s I had written down (of which there are many):

“Even when you feel lost, you are never not on the path.”

Having taken after my late teacher, I’ve lived as a hermit-poet for over a decade now, “down in the city, behind the courtyard wall,” as some of the old Daoist and Chan poets who followed this same pattern might’ve said. I am ever-oriented to the unique cross-pollinated creative and spiritual path my teacher shared with me, and this is often reflected in my poetry. I have come to think of this ongoing curriculum as ‘the school of soft-attention.’

Ultimately, whether writing one of my own poems, or steeping in the words of someone else in this unofficial cross-cultural lineage of crazy clouds and wayfarers, it is a thoroughgoing path of sourcing within the flow of the Great Transformation of life, slowly finding a sense of peace inside one’s own skin. I hope some of the poems in The School of Soft-Attention can support you, dear reader, in doing the same. Perhaps one of them will inspire you to turn toward your life in a new way, with a new way of looking, a new way of seeing, a new way of paying attention to the seen and unseen life within and around you.

Frank LaRue Owen

near the Natchez Trace

Michiziiibi (Mississippi)

When Your Spirit Eyes Are Tired

You have two sets of eyes

the physical ones

and the vast eyes

placed within you

by the spirit land

through which you move.

You may think

the rocks and trees from your land of birth

are just rocks and trees of your land of birth

but your second set of eyes are on loan from them

and unseen fearless things around you

that you can never fully understand.

If you awake one day

with tired spirit eyes,

pay heed;

that’s a different type of fatigue

a signal arriving

from your own ground of being

telling you in no uncertain terms

that a big rusted lock

is about to be busted open within you.

The question The Teacher will ask

on the path between mountain top and parking lot:

Are you brave enough

to embrace what awaits

on the other side of the door?

Forest Bathing

There is a way of entering the forest

when the breeze of the trees

becomes your guide

when the cool gray-green days

and humid blue-green nights

become your own skin

where the unfurling paths

through the emerald light

become flowing streams.

Paths as luminous rivers

for your two uncovered feet,

salmon-like and aching,

to work out their

strange haunted yearning

for a home

whose vista

they haven’t yet seen

yet somehow know

just the same.

There is a way of approaching the self

without a heavy hand

when the heart-mind

slowly becomes unburdened by the past,

where the body

listening with the whole of itself

finally becomes attuned

to all the subtle happenings

in the realm not yet stained

by the faithless world of man.

Cradle of Sunlight

I went to the well tonight to draw water

looked over the edge, down into the darkness

that has always been a reliable mirror,

a quencher of deep thirsts.

It was empty.

At first, it made me think of my Irish ancestors

and all their striving and starving and yearning and stories…

of how old wells could run dry

and the underground rivers that fed them

could ‘Up and Move’

if someone hadn’t honored them, properly.

I wondered what ancient river inside of me

I had ignored for the water of life to run dry on a rainy night.

Then, I realized the vision wasn’t about me.

Like the Hawk of Achill taking flight,

the eyes of my heart-mind were whisked up

on the high winds of night.

I was carried across nine glowing waves

and shown a moment in time

when life made more sense;

when there was a magic order to things

and every moist day was saturated in mystery.

I needed to see that, freshly, to be able to see you, clearly.

Time has passed.

You’ve taken your warrior-self on another adventure.

Tenacious. Beautiful.

Fighting your way through as usual.

And now I know,

that this place is the empty well

and you are the life-giving river that has moved on

because you were not honored here.

This is not a poem…even though you asked for one.

It is a katana-prayer slicing through air.

My deepest wish for you

is that the deepest parts of you

can one day put down the battle

and let yourself truly be held

in a cradle of loving sunlight.

Now Available

Temple of Warm Harmony

Trade Paperback | Size: 6 x 9 | Length: 128pgs | List Price: $16.95

The Temple of Warm Harmony is a book of poems, but it is also something of a map. Some of the poems are about the author, some are about the reader, while other poems are about the times we’re all living through. A blend of mini-exorcisms, healing incantations, dreams, and invitations to numinous ways of observing and experiencing life, the book is divided into three parts: In the World of Red Dust, Heartbreak and Armoring, and Entering The Temple of Warm Harmony. On the heels of his award-winning first book of poetry, The School of Soft-Attention, poet Frank LaRue Owen invites “fellow travelers” to consider ways we can regain a sense of harmony even while navigating challenging terrain, personally and collectively.

_______________________

Available in Paperback and ebook.

*Receive 20% off when you purchase in our store

+ Free shipping on orders over $40.00 with coupon code: INDIESTRONG

Get In Touch

(860) 574-5847

info ‹at› homeboundpublications.com

Postal Box 1442, Pawcatuck, CT 06379-1442

Passionate about independent storytellers? Join the circle.

Reach out to us . . . Send an email. (GASP) Pen a letter. Reach out to our authors. Ask a question. Tell us your story . . . Donate toward our future (if you are so inclined) . . . Just reach out to us. We are a community, not a company and you are a part of that community.