Will Falk

Will Falk (he/him) is a biophilic author, attorney, and activist. The natural world speaks and Falk’s work is how he listens. He believes the intensifying destruction of the natural world is the most pressing issue confronting us today and he aims his writing at stopping this destruction. He is grateful to the places and countless creatures who have nurtured his writing. These include the Bayview shore of Lake Michigan in Milwaukee, WI; the Unist’ot’en Camp on unceded Wet’suwet’en land; sacred Mauna Kea; pinyon-juniper forests wherever they are found; the Colorado River; and Peehee mu’huh (Thacker Pass).

A former Wisconsin public defender, Falk’s law practice is now devoted to protecting as much of the natural world as he can. His first book, How Dams Fall—a short work of creative nonfiction about his relationship with the Colorado River—was published as part of Wayfarer’s Little Bound Books series in 2019. Falk hopes his poetry will help his readers fall in love with the natural world and, once in love, to protect their beloved. You can follow Falk’s work at willfalk.org and on Substack.

About

Many poets write about the natural world–few poets write while acting directly to defend the natural world like environmental activist and attorney Will Falk does in When I Set the Sweetgrass Down. The natural world speaks, Falk insists, in these biophilic poems written from the frontlines of land defense campaigns. These poems are a record of what Falk heard from the natural world in places like Thacker Pass, Nevada where Falk set up a protest occupation in a beautiful mountain pass set for destruction by an open pit mine and Hawaii’s Mauna Kea where Falk helped to blockade telescope construction from desecrating the sacred mountain. At a time when the destruction of the natural world is intensifying, When I Set the Sweetgrass Down will help readers find the courage they need to–and remind them why they must–act to defend the source of all life: the natural world.

Videos

Will Falk reading “How We Got Here” published in Wayfarer Magazine 2024.

nonfiction

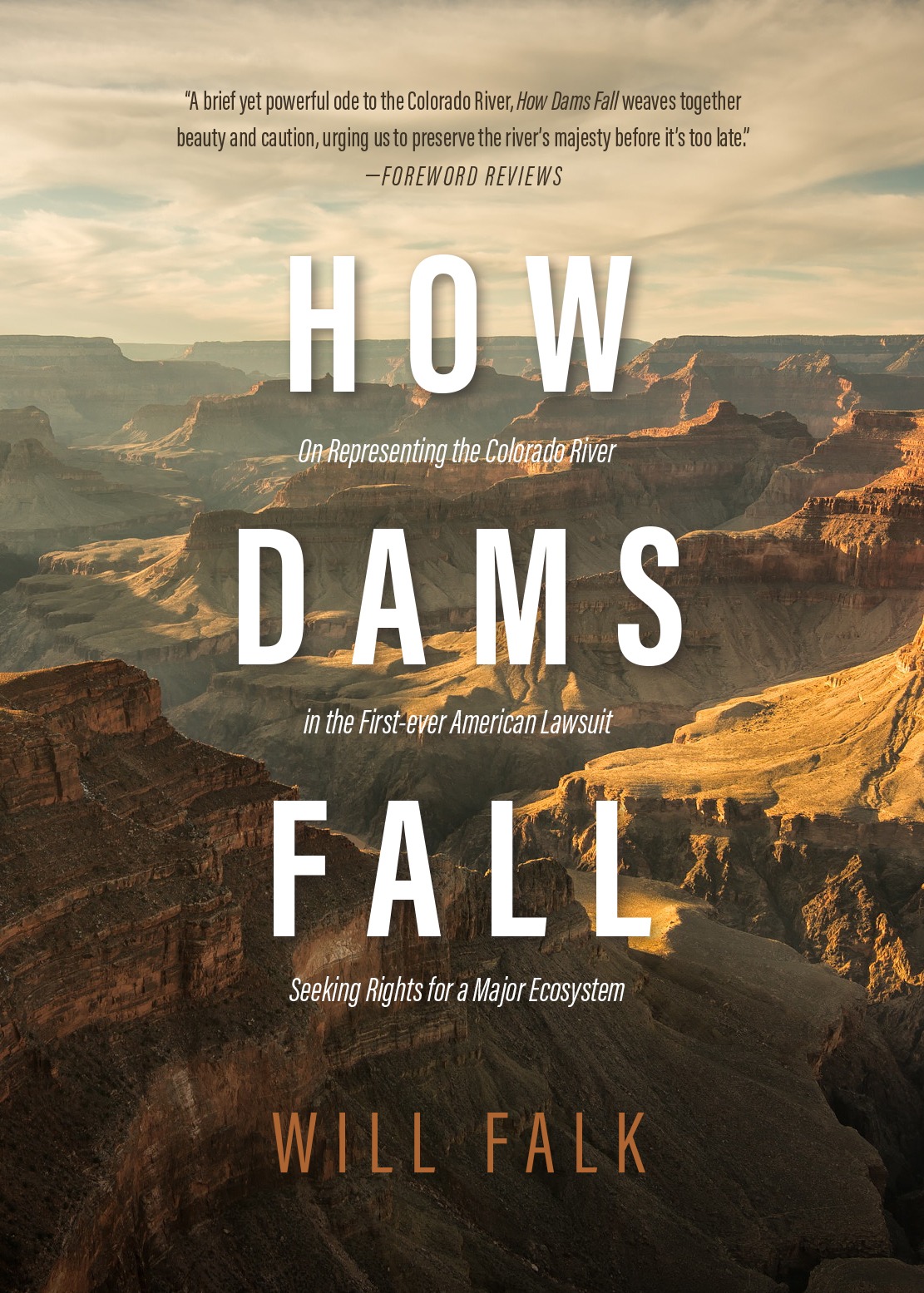

How Dams Fall

On Representing the Colorado River in the First-ever American Lawsuit Seeking Rights for a Major Ecosystem

Also Available on Amazon – US & Global > B&N > Bookshop.org > Apple > Walmart > Target > Waterstones > Betterworld Books > In Your Local Bookstore

Praise for How Dams Fall

“Heartfelt and poetic, Falk channels the wisdom of Nature, offering readers a profound call to rethink their relationship with the Earth.”

—David R. Boyd, author of The Rights of Nature

“With poetic grace and fierce passion, Falk will make you fall in love with the Colorado River, break your heart, and leave you forever changed.”

—Max Wilbert, author of Bright Green Lies

“A lyrical love letter to a living ecosystem, How Dams Fall is a poignant exploration of stewardship, survival, and the hope of healing.”

—Johnny Worthen, author of What Immortal Hand

“In this intriguing account, Falk’s relationship with the Colorado River exemplifies a new breed of advocates for Earth, reminding us of the river’s timeless majesty.”

—Cormac Cullinan, author of Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice

“A piercing elegy for the Colorado River, Falk’s journey refuses false hope and instead offers unwavering love for the river—and a call for all of us to join him.”

—Lierre Keith, author of Deep Green Resistance

find our titles

Every book you buy directly from us sidesteps billionaire-backed retailers and helps keep marginalized stories alive in our community.

We’re a queer/trans-owned indie press, and while our books are technically everywhere (paperback, ebook, and audiobook at local shops, Bookshop.org, iTunes, Barnes & Noble, Walmart, and Amazon) we’d much rather you support indie, queer, trans, Indigenous, immigrant, and BIPOC-owned bookstores, or buy direct from us at wayfarerbookstore.com.

Wholesale inquiries? Wayfarer titles are available through Ingram with standard trade terms and lifetime returnability, with print bases in the US, EU, UK, and Australia global fulfillment.

we are on native land.

Wayfarer Books is based in the San Juan Mountains near Mesa Verde, on the lands of the Ancestral Pueblo, the Southern Ute, the Mountain Ute (the Weenuchiu), the Diné (Navajo), and the San Juan Southern Paiute Nations. We honor the generations of Indigenous communities who have lived in, stewarded, and maintained these lands for thousands of years. We recognize that this land was taken through colonization and displacement, and we acknowledge the ongoing presence and contributions of Indigenous peoples, past, and present. As a company rooted in stories and knowledge, we commit to listening, learning, and supporting Indigenous voices, sovereignty, and wealth redistribution.