Publisher of Independent Since 2011

indie Lit Since 2011

About us

Homebound Publications is a Trans/Queer Owned publishing house based in the Berkshire Mountains. What began during a brainstorming session in a Boston cafe has become a platform for hundreds of indie authors. More than a company, we are a community of writers and readers exploring the larger questions we face as a global village. We publish full-length introspective works of creative non-fiction and poetry.

About us

Homebound Publications is a Trans/Queer Owned publishing house based in the Berkshire Mountains. What began during a brainstorming session in a Boston cafe has become a platform for hundreds of indie authors. More than a company, we are a community of writers and readers exploring the larger questions we face as a global village. In conjunction with our sibling press Wayfarer Books, we publish full-length and serialized introspective works of creative non-fiction and poetry.

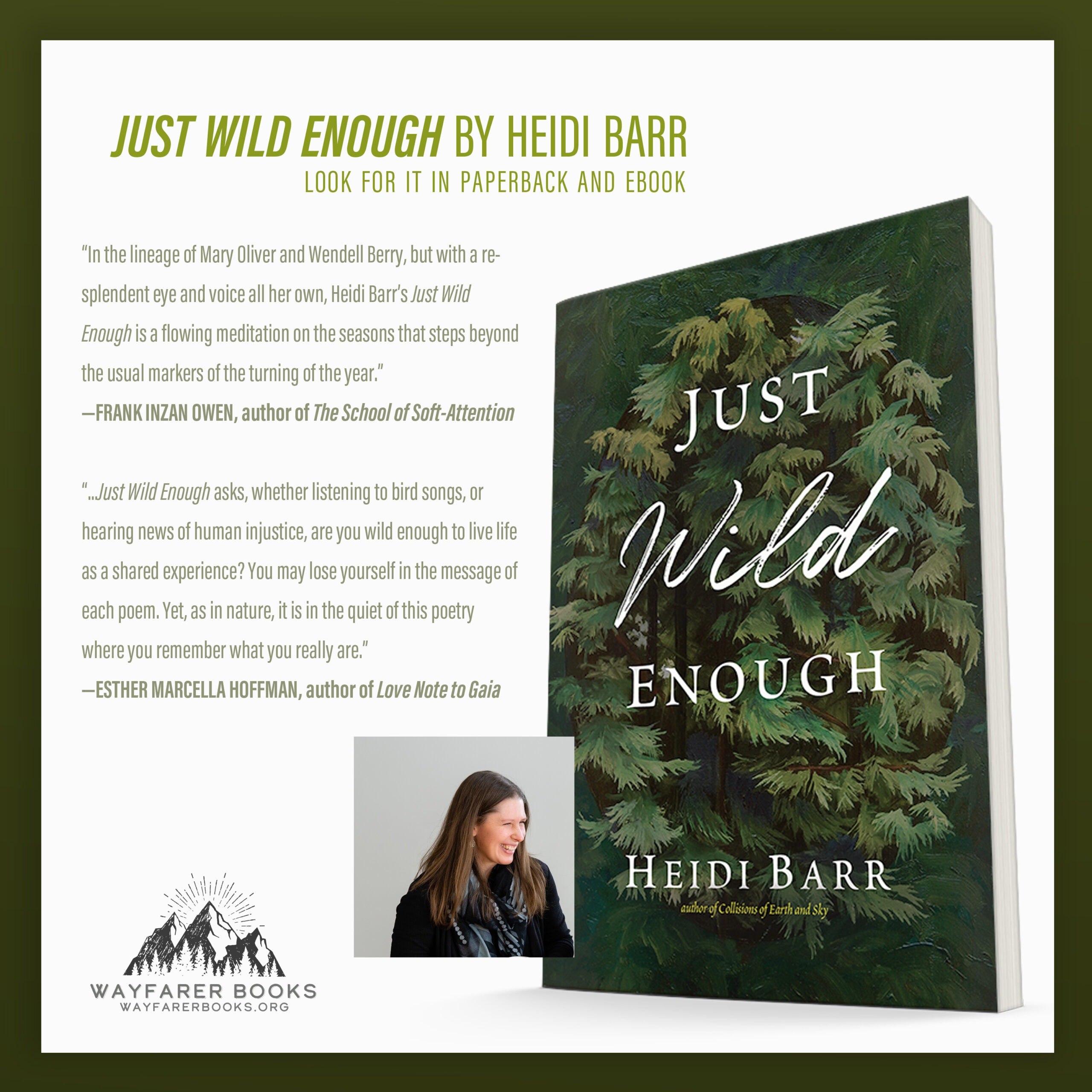

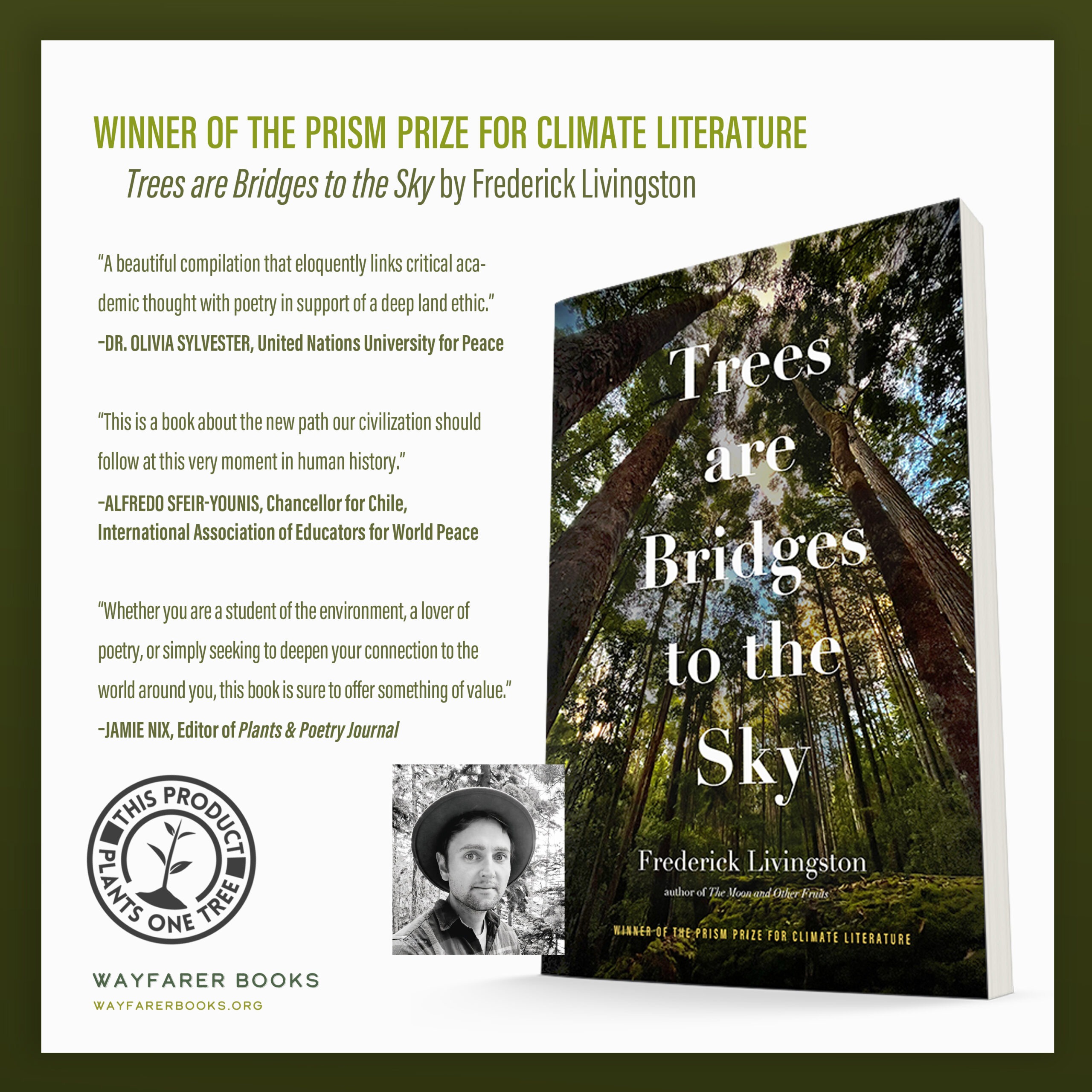

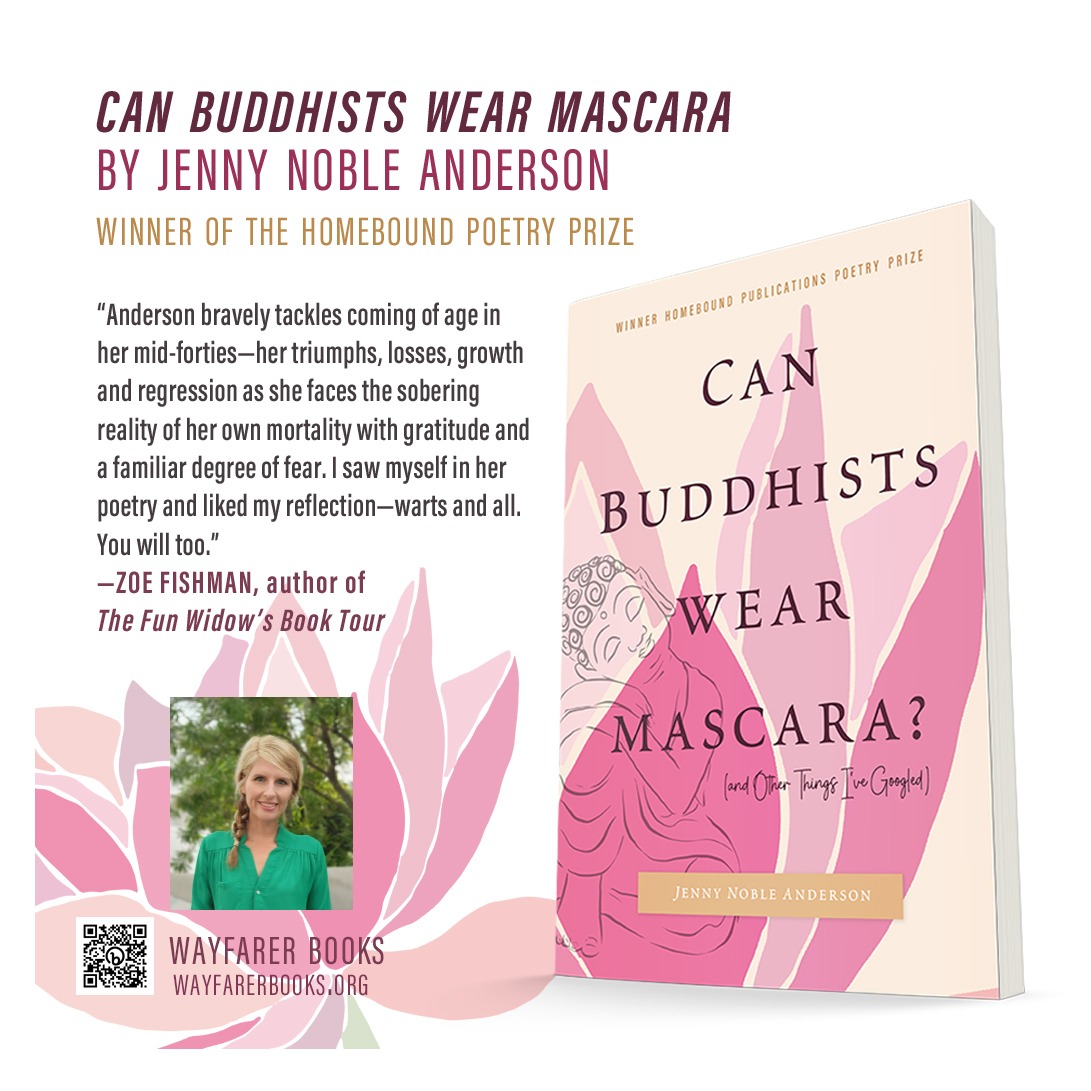

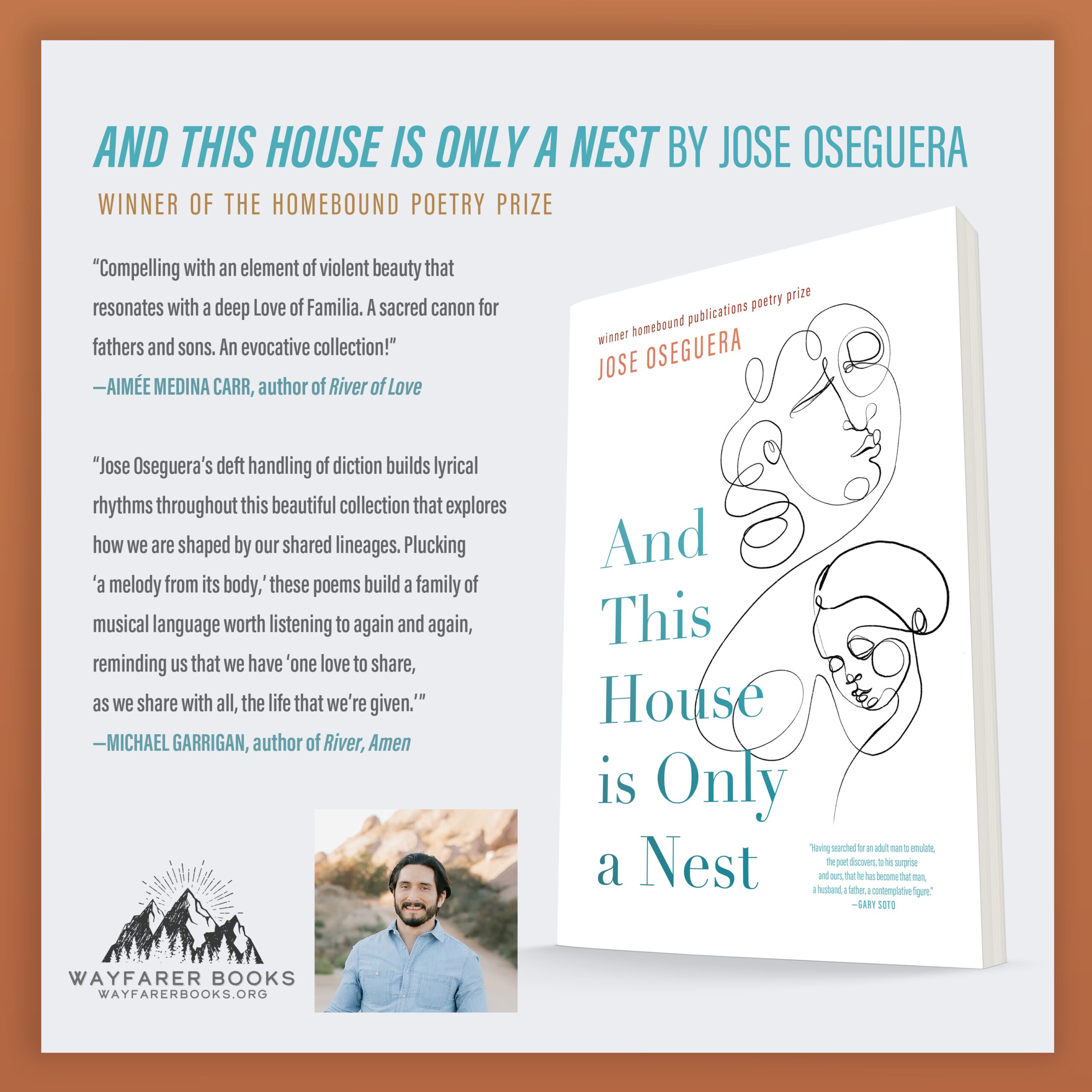

featured titles

explore our

mission

At Homebound Publications and Wayfarer Books, we believe poetry is the language of the earth. We believe words—like rivers through wild places—can change the shape of the world. We publish poets and writers and renegades who stand outside of mainstream culture—poets, essayists, and storytellers whose work might withstand the scrutiny of crows and coyotes, those who are cryptic and floral, the crepuscular, and the queer-at-heart. We are more than just a publisher but a community of writers. Our mission is to produce books that can serve as a compass and map to all wayfarers through wild terrain.

about our

mission

At Homebound Publications and Wayfarer Books, we believe poetry is the language of the earth. We believe words—like rivers through wild places—can change the shape of the world. We publish poets and writers and renegades who stand outside of mainstream culture—poets, essayists, and storytellers whose work might withstand the scrutiny of crows and coyotes, those who are cryptic and floral, the crepuscular, and the queer-at-heart. We are more than just a publisher but a community of writers. Our mission is to produce books that can serve as a compass and map to all wayfarers through wild terrain.

explore our

mission

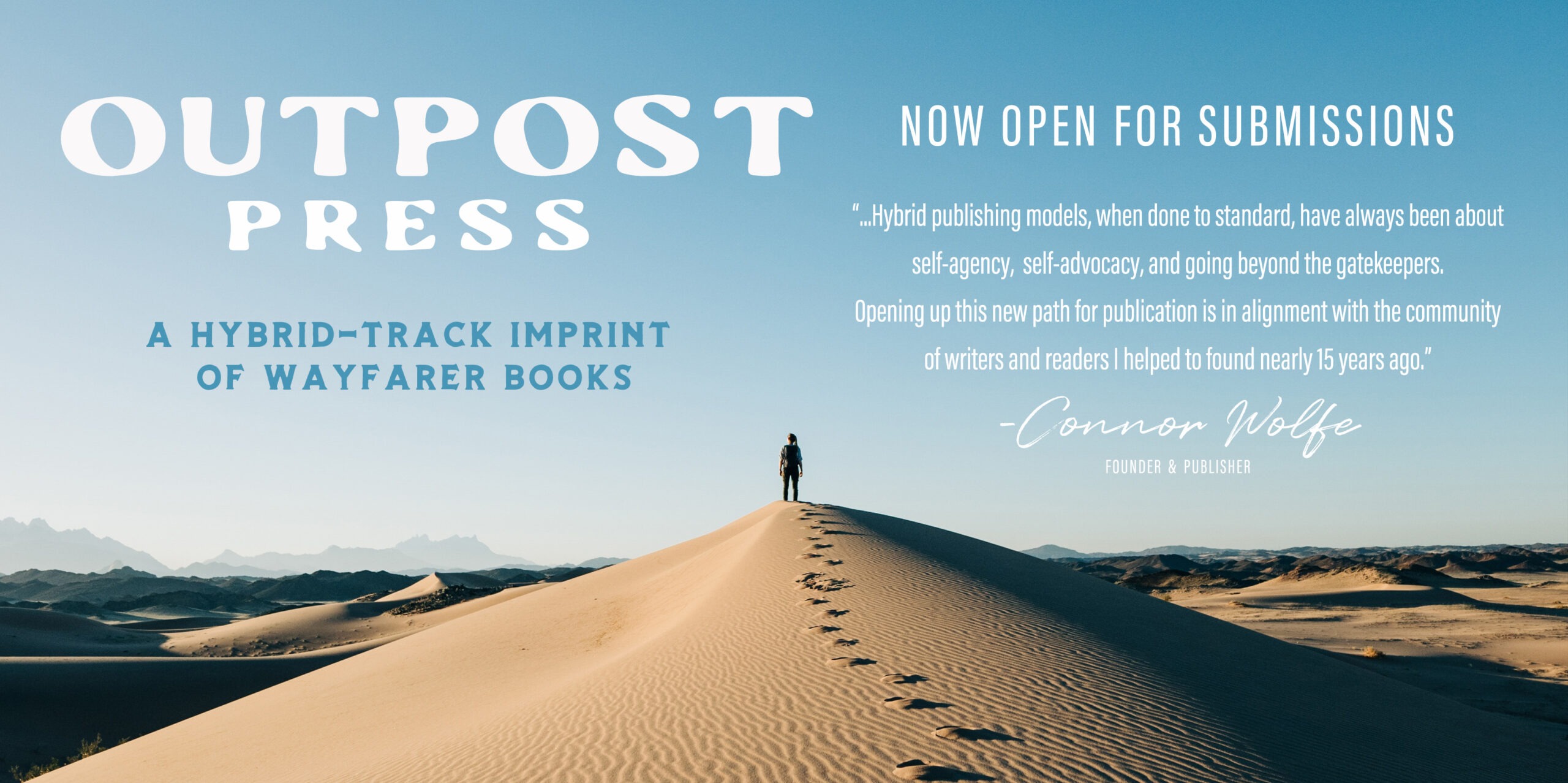

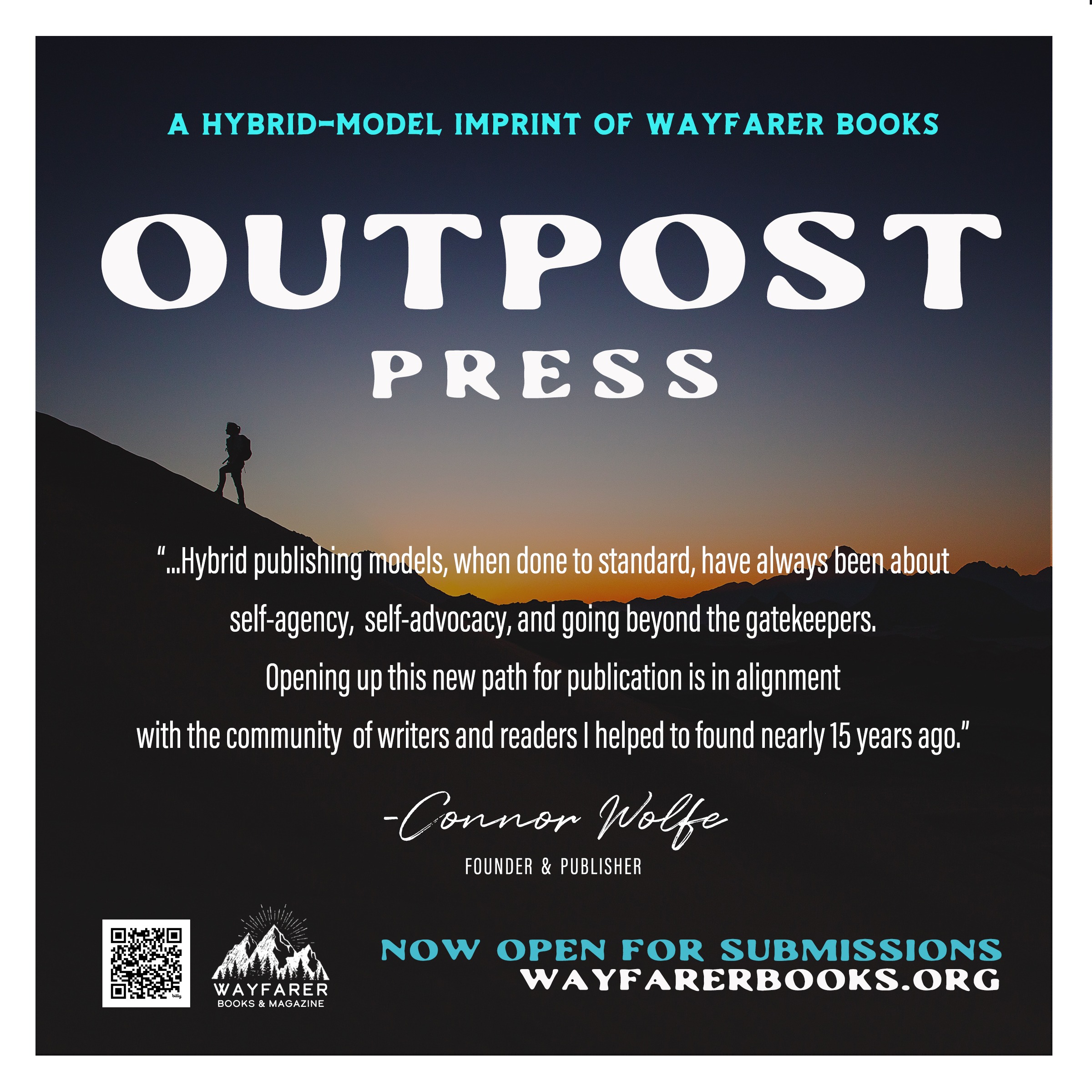

OUTPOST PRESS Is our latest imprint offering a hybrid route for those authors who are willing to subsidize their own project to help shoulder the financial investment in the project, allowing us to take on the project that would otherwise be impossible due to lean budgets. Wayfarer Books’ Hybrid Track is operated as a PTO/POD model; we print through Ingram and have wholesale availability to the trade retailers (Amazon, B&N, Indie Bookstores, etc.) via Ingram. And, as with all our imprints, We offer our titles at the standard terms expected by retailers from the larger houses (45% – 55% Discount and Full Returnability).

about our

mission

OUTPOST PRESS Is our latest imprint offering a hybrid route for those authors who are willing to subsidize their own project to help shoulder the financial investment in the project, allowing us to take on the project that would otherwise be impossible due to lean budgets. Wayfarer Books’ Hybrid Track is operated as a PTO/POD model; we print through Ingram and have wholesale availability to the trade retailers (Amazon, B&N, Indie Bookstores, etc.) via Ingram. And, as with all our imprints, We offer our titles at the standard terms expected by retailers from the larger houses (45% – 55% Discount and Full Returnability).

The latest

be in the know without the social media

Contact

Homebound Publications is distributed by Publisher’s Group West, a Division of Ingram Publisher Services.

Find our titles in paperback, ebook, and audiobook formats, wherever books are sold.

Location

Northampton, Mass.

orders@homeboundpublications.com